Paris Photo Beauty. No. 71 (1966)

Born in Toulouse in 1927, Serge Jacques became interested in photography as a hobby while still a student at the Lycee Carnot (high school) in his home town. He later went on to the Ecole Suisse in Geneva, where he studied professional photography. After further studies in Munich, he returned to France and in Paris became an apprentice to a fashion photographer. For some months he drifted from job to job as an assistant, never staying long at any one studio. “I was afraid that if I worked too long for the same man, I would tend to imitate his style,” he says. “I was determined to develop my own.”

In 1950 he did his first nude, a female figure silhouetted behind a window. It was published in Paris and soon magazine editors began to assign him to work with the fabulous models of Paris. After publishing a successful album of nudes, he opened his first studio the next year-a cavernous cellar on the Rue de Belleville, but it had some significance for him. His parents had a theatre, the oldest in Paris, on the Rue de Belleville and with their help he established connections that were to make him the foremost photographer of French show business, mainly night clubs.

A year later he moved to his present studio on the Boulevard Malesherbes. From this vast complex of shooting areas, offices, darkrooms, more than 10,000 photos a· year go out to be published in newspapers, magazines and books around the world. The studio file comprises over 200,000 negatives. He has attained an international reputation as a photographer of the nude, with hardcover albums published in France, Germany and Scandinavia. He has also exhibited modern portraits in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris and in Copenhagen.

Jacques is often asked for advice by young people seeking a career in photography. “I would tell every young man to prepare himself for sacrifice,” he says. “Don’t be a photo salesman. I still don’t know how to sell a photograph. You have to shoot with honesty, with the artistry of the final picture in mind. If you do this, you will develop your talent and your own style and you won’t have to sell. Somebody will buy.”

When .Jacques feels that he has the time and uses his own model instead of a passing girl for his candid shots, he switches to 2¼ x 2¼ film size. He made use of several Rolleis. Nikons, Hasselblads and Canons from his large collection of cameras. With the 35mms. however, he generally uses an 85mm or 105mm lens, so that he can get back a greater distance from the model.

The photographer always tries to fit the girl to the location. For example, on the bench along St. Germain, tomboyish Anouk Aimee was his model. Teenager Annette Meran rides the bus and shops for paperbacks along, the Quai d’Orsay. Tiny China, standing among the motorbikes, represents the Cambodian contingent. On the Seine is seen blonde Janine Orielle.

Paris is noted is apparent here. “Elegance?” he asks. “Not Paris in the daytime… not my Paris. My Paris is young, gay, informal and exciting. It dresses to stroll along the Seine with a lover, not to go to the office or the opera.”

Serge Jacques was born into the creative purple. His parents owned the Theatre de Belleville in Paris. But it was on holiday in Corsica, as an 18-year-old, that he took his first step along the photographic path. “I was on top of the bed with my girlfriend. She up suddenly, to look out of the window, and I took a picture of the shadow falling across her body. I then took similar pictures of all my girlfriends, for fun. Then a magazine editor asked me if I could let him have them all to publish in a book.” Club International. Vol 13 No 11 (1984)

In view of the vast number of beauties with whom Serge Jacques has worked over the years, he frankly admits that he has had a great many models in his studio who were by his standards “ordinary,” even though to an average reader they might seem spectacular when they appear on the pages of magazines. There are, nevertheless, certain individual models among the many hundreds he has photographed, whom he docs consider his favorites, each of them for some specific reason. Sometimes it is because she is especially easy to work with (models being notoriously temperamental); sometimes because she has helped him to score a notable success with a publication; sometimes because she is blessed with a special, rare type of beauty which contributes to his esthetic satisfaction as an artist.

Although glamor photographers work with some of the shapeliest bodies in the world, they regard portrait work as the most exciting and challenging aspect of their profession. Says Jacques. “A body is primarily sculpturesque. Beautiful, yes, yet in a larger sense, inanimate. But a face—ah, a face is alive; it is the woman herself! Only a face has anything new to offer—nuances and surprises. Most of my best work is due to the model’s face.”

It is only natural that Jacques’ work in this area is largely candid. Rarely does he do the so-called traditional type of portrait, in the studio under fixed lighting conditions. At such times this would be part of a larger series, ordered specifically by a client. Even then, he will shoot candid portraits and present them to the client for a comparison, often thereby converting the client to the value of candids.

But candid portraiture has its pitfalls. In the studio the photographer can control his lights: in candid work, particularly outdoors, he risks harsh, intruding shadows. Jacques feels that only in the candid approach can he find honesty, because the artificial atmosphere of the studio tends to inhibit the subject, with resulting stiffness due to self-consciousness. Furthermore, controlled lighting is a mixed blessing. For it is the rare model whose skin is so flawless that it can stand the glare of flood lights for a close-up without cosmetics. Jacques insists on the minimum of makeup for a model—a touch of lipstick, a trace of eye shadow, and that’s all.

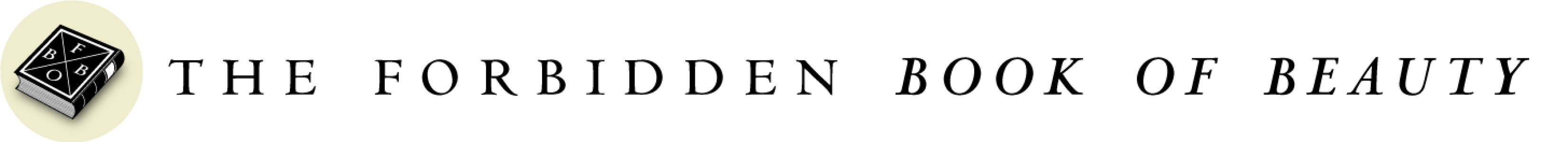

A fine photograph of the nude is not merely a filmed representation of the unclothed form, as a study of Serge Jacques’ work will attest. There is a distinctiveness that stamps his pictures. It is often the elegantly arched attitude of the model against part of an outdoor setting; in the studio it may be the outlandish prop that creates a piece of modern art. These stylizations have not been achieved by pure chance, but are the products of years of strenuous trial and error with hundreds of models, thousands of rolls of film, dozens upon dozens of different combinations of aperture openings, depths of focus, shutter speeds, etc.

Long ago Serge Jacques discovered the optimum situation for shooting nudes: the great outdoors with its natural settings and natural light. “No matter what you do,” he says, “there is a comparative harshness to photography done indoors. At least three-quarters of all my work is done outdoors, shooting with the shadows created by the natural illumination of a bright, sunny day. Every year, when the weather turns bud in Paris, I go south to the Riviera or to southern Spain, where it is warm and I can continue my shooting outdoors.”

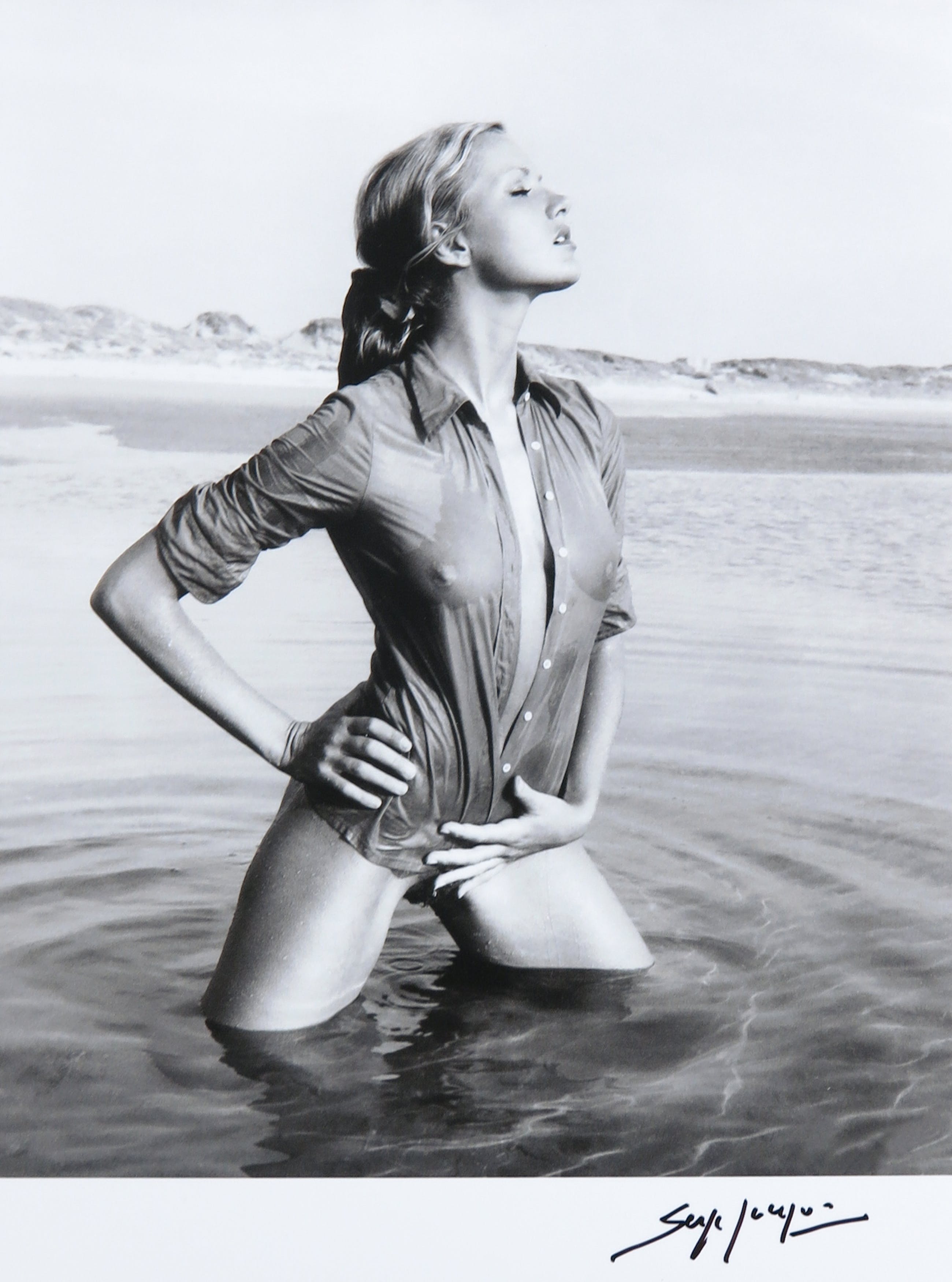

One of Jacques’ favorite outdoor poses is of a girl partially submerged in water. “Wet skin prints up with a very exciting quality and the reflection of the water can be used to excellent advantage. Also, a model, experienced or not, will find that working outdoors in a water setting gives her a certain feeling of freedom and exhilaration… and this shows up in the finished picture.”

“Often,” he continues, “I deliberately take extra time in setting up my cameras when an outdoor shooting session starts. I tell the model to go, run around and enjoy herself while I get ready—to take a swim or something—to just relax and be happy and carefree. This helps her to get into the right mood for the shooting, to free herself of clothes and also of inhibitions and artificiality. There are times when I suddenly grab a camera and begin shooting while the model is frisking about like that. Some of my best photos have been captured candidly while the model was not actually posing. This has especially been the case with new, unprofessional models.”

Shooting in the studio, with its positive maze of lights, props and other equipment, is a different proposition entirely. Color is easier to shoot in the studio, but in black and white the problem indoors is composition. You can do just so much against a roll of paper and that’s it. No matter how supple the model’s body and how beautiful her face, there are limits to the variety of poses and angles within a confined area.

Jacques’ approach to photographing Paris at night is different, involving its own distinct attitude and equally distinct technique. One most important advantage is that he has entree to, and has shot pictures of the interiors of, more night clubs in Paris than any other photographer in the world. He has had virtually entire shows rerun for him exclusively, so that he might set up his own lighting arrangement and do a thorough job in his own way.

However·, for the most part he prefers to shoot night clubs and their shows by existing light only, using a 35mm camera. He feels that for magazine publication, this retains a candidness and effective realism in the pictures. It is because he is willing to work so much in existing light, and with such excellent results, that he easily gains entree to the clubs. Managers feel that he photographs their shows to maximum advantage with a minimum of bother to performers or stage crews.

When the normal artificial stage lighting is intense enough, Jacques makes his exposures with lens apertures of f:4 or f:5.6 and shutter speeds of either 1/60th or 1/125th of a second. If absolutely necessary, he will use the lens wide open, but thereby runs into the depth-of-field problem.

On the walls of Serge Jacques’ studio on the Boulevard Malesherbes are photographs of dozens of budding young starlets who stand on the threshold of fame. Jacques is justly proud of this array because in most cases he was the first to photograph them. It is impossible to look at a girl, whether she has previous professional experience or not, and say, “This is a star of tomorrow,” with assurance. One cannot advertise for her or visit the office of a theatrical agent of a motion picture studio and pick her out from among a new crop of beauties.

It requires a quite different process. The photographer’s instinct and experience finds for him, among the hundreds of girls he meets and photographs, those precious few who possess some special quality, some vital spark, that makes them stand out among the rest. It is not a tangible thing like beauty, or measurements, or a nose, or hair style, but rather, as Jacques says, a “Je ne sais quoi”-an indefinable “something” that shines through in her personality. This is what Jacques senses when he meets such a girl.

It may be expressed in the way she carries herself, or some spark in her eyes of which she herself is not conscious. It can be a smile, a toss of the head as she talks—something that comes from within, shining through like a beacon for an alert photographer to spot. When he meets such a girl, it behooves him to treat her with extraordinary care. Regarding such a gem as just another model can be ruinous for her and the waste of a rare find for the photographer.

“When I am fortunate enough to find, or think I have found, a girI with that special quality that I talk about,” Jacques says, “I try to make an exclusive contract with her. But, business aside, I try to discover for myself what it is that makes her so different from the others. Then I do everything possible to bring out that special appeal in her photographs.”

In his search for future stars, Jacques wanders all over Paris. He spends a great deal of time around the night clubs, where there is a constant influx of new talent; he searches the art schools and the dancing academies, where his eye scans the budding ballerinas. But most of the time, he just walks and looks, because, more often than not, he finds his rare gem in the most unlikely place.

While Jacques is partial to backgrounds such as beaches and rocks, he does not ignore the many other natural settings that are available. Each outdoor area presents its own problems, of course. In heavily wooded localities the photographer might find the abundance of foliage a distraction or, if he is using color, overpowering in that respect. The trick is to use this to good advantage. Nothing enhances the figure of a beautiful model more than the designs and colors of nature, no matter what time of year.

Imagine such things as the diffused sunlight as it filters down through a leafy tree to cast an intriguing pattern of shadows over the subject’s face and body… or the model in the background as you shoot through the hanging branches of a willow or through a spray of wildflowers, with the foreground slightly out of focus. Nature also helps to overcome the problem of what to do with her hands, because even the most

When the model possesses an exceptional figure as well as face and she also has the grace of a dancer, a full day outdoors can be spent with her alone. Such a model is shown here in some of the hundreds of shots on the beach. All the work was done in natural sunlight, which varied in intensity during the day.

The Great Advantages of Natural Light

To Serge Jacques, the predictable result of shooting in natural light is the production of photographs which have a natural quality. Even indoors, he relies on natural illumination for the most part, resorting to artificial sources only when absolutely necessary.

Outdoors, where he prefers to work, he finds few problems with natural light. He takes pains to avoid direct overhead, sun, preferring it to come from behind or from the side of his subject. With the face in shade from an oblique, slanting sun, he gets results that are soft and marvelously effective. The model’s hair, particularly if she is a blonde, glows as though haloed and the face is devoid of harsh shadows. If he finds it difficult to pose the model in the sun, he will shoot entirely in the shade (which he sometimes does throughout an entire session), assuring himself thereby of soft, flattering gradations of tone.

One technique that has proven particularly valuable when shooting in bright sunlight is to have the model throw her head back and away from the sun, softening all the tonal values to a point where they are pleasing. Actually, he prefers to work outdoors when the day is completely, but not too heavily, overcast, thus avoiding the problems of direct sun.

Jacques insists that he can produce better tones and minimal shadow interference by using natural light when he is given a free hand. The depth and naturalness of his photographs done with natural light are indeed superior to those taken with artificial illumination.

The best single source of natural light is usually a window, which produces sharp, clear photos and yet is not so strong as to destroy the depth and tone sought in glamor photography. Close-ups, particularly, come out dramatically when this source is used, because Jacques works with a wider lens aperture and less depth of field, thereby avoiding distracting backgrounds.

“The whole mood of a shooting session is more relaxed,” be says. “The model is less inhibited in a naturally lighted studio or room, whereas she often feels intimidated by complicated strobe units or floods.”

Generally, Jacques shoots the full figure indoors with small lens openings and slow shutter, risking camera or model movement in order to retain a sufficient depth of field. For close-ups here he opens up the lens to f:2 or even f:1.5, al though they give a shallow field. “When I concentrate on the face I sometimes even throw an ear out of focus,” he says. “I am aiming for expression in the model’s face. With natural light I can advance my film in a fraction of a second and get varied expressions as though using a sequence camera.”

Perhaps above all other rules which he considers important, Jacques follows the one: “Go prepared.” When on an outdoor photo expedition, he carries everything that he owns in the way of outdoor equipment. “Better overburdened than undergunned” should be the slogan if you want to be able to take advantage of an unexpected situation, should it suddenly present itself.

Source: Paris Photo Beauty. No. 71 (1966)